Via a reliable airport – where I bought a ticket on my temporary passport – I left Central Africa. I took a scheduled flight to North Africa. In North Africa, I travelled by public transport to Alexandria. I recollected my normal passport at friends. I stayed a week with them; we talked about the events in our lives.

[1]

[1]

In the Alexandrian library, I carried out a small part of my desk research on sources for the reporting of this study trip on the causes and consequences of genocide in Central Africa. It was honour for me to perform this research in the Alexandrian library. The predecessor of this modern library was destroyed in classical antiquity by several fires. Many classic books from the Greek and Roman antiquity were forever lost in these fires. Research on my sources had amongst others the aim to give the lost lives by genocide in Central Africa a place in history.

[2]

[2]

I entered South Europe with a ferry. A train journey of more than a day took me back to the Netherlands. Here I could write my report during my recovery of a tropical disease.

Through my game of hide-and-seek during my stay in Central Africa and by my very causious return to Europe, no-one could easily link me to my research. I am still glad that I took these precautions, because one cannot be too careful with helpers of dictators, with arms dealers and secret services of various countries.

During this long trip, I organised the many impressions that I gained in Central Africa. Obviously I have already sorted out my research data, but in the plane, on the boat and in the train, the mainlines for the reporting of the study tour took a clear shape.

I decided to split the reporting of the events in four parts. The first part focused on culture or the behaviour of groups – perpetrators or victims – that were directly involved in the genocide. The second part covered the influence of individual behaviour of offenders, rulers and opinion leaders on the genocide. The third part described the influences on the excesses caused by organisations, bodies and countries outside Central Africa. This third part is confidential: it contains my findings on the impact of arms deliveries by traders and countries with political interests in Central Africa, on secret services with their sometimes obscure matters and the inability/negligence of international bodies. The last part of my report covered the potential legal liability of individual parties for their part in the genocide. During criminal investigation into the genocide, excavations were carried out and further research took place on the basis of my report.

[3]

[3]

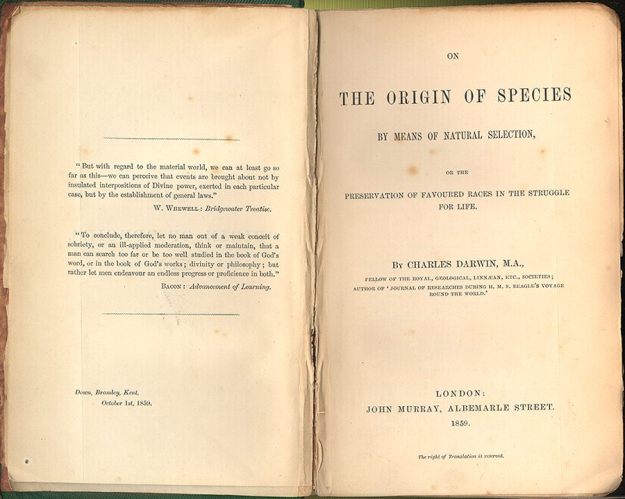

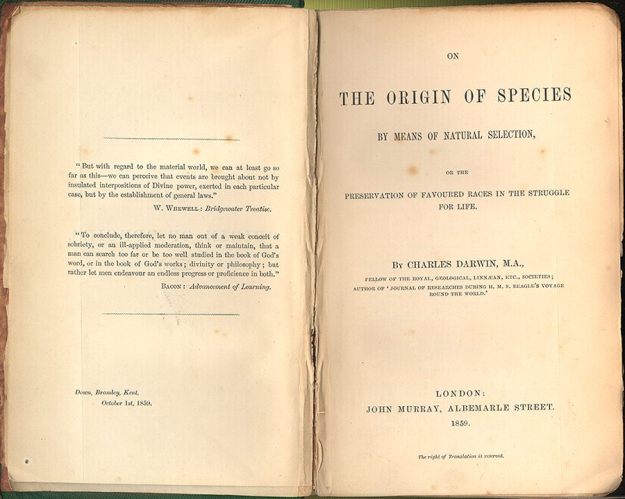

Before this study trip in Central Africa, I had looked upon cultures as a way whereby groups of people – including its individuals – live together en behave together. A culture was a “Modus Vivendi” of a coherent group of people. Obviously a culture changed over time, for example by changed circumstances or by migration of outsiders. But I had not linked culture with a living organization that – just like any living creature – was engaged in a “Survival of the Fittest”, as described by Darwin in “The Origin of Species”.

[4]

[4]

In the unfamiliar surroundings of Central Africa and on the basis of conversations with residents, I started to see more and more clearly that a culture can be compared to a living being that is always busy with survival. During the development of this idea, I noticed parallels in the history of the Western world.

In the first part of my report, I described that culture is endemically present in an individual, within a family, a village community, a tribe/group/people living in a coherent area. In Central Africa, the Nations as legal body were still in its infancy: the national culture was hardly developed. Cultures are a way of living together – a Modus Vivendi –, which provides stability and confidence. On the other hand, cultures struggle for survival and try to impose a certain behaviour to insiders; outsiders are convinced of the right attitude of a culture and – either temporarily or permanently – included in the culture or they are excluded.

Cultures are not static, they change over time as a language changes with the change of its speakers. A well-known and familiar mother tongue from a hundred years ago sounds strange/familiar to us similar as the way of living of people from a hundred years ago appear strange/familiar. Many of these changes gradually take place by assimilation or by organic growth.

A culture is not homogeneous and uniform. Within a somewhat extensive culture there is almost always a layering or stratification present. A culture also has internal tensions between mutual subcultures.

Sometimes, for example, by major changes – by a population explosion or by an important development – or by very small coincidences during potential turning points – bifurcation points within the chaos theory – shifts can unexpectedly take place within a culture [5]. This rapid growth can cause stigmatisation, exclusion or destruction of dissenters within the own culture.

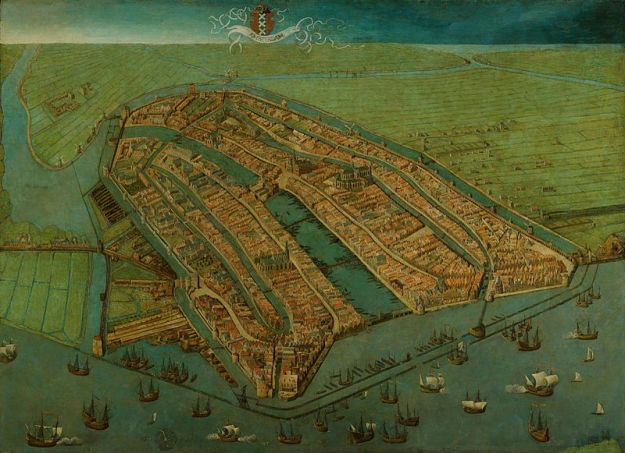

The discharge of the tensions can also take place by excesses against other (sub-) cultures. Usually cultures live in reasonable co-existence as good neighbours. Occasionally, there are differences of view that are made bearable by diplomacy, festivities, words, case law and treaties. Sometimes the tensions between cultures lead to eruption. The cause can be: a strong change in mutual relationships, a smouldering injustice from the past that manifests itself in a conflicts caused by a sudden incident. These eruptions can lead to violent outbursts. The Pax Romana around 400 a.d. in the area of the Danube is an example from the history with an ill-fated end. In Danube area, the Romans conducted a policy of divide and emperor where the favours were unequally divided between the separate cultures so that the mutual envy was greater than the tension with the Roman imperator. Once per generation, a culture was violently stripped of its wealth by the Romans and several of its allies. In general it took a generation before the culture could recover from this blow.

Around 400 a.d., the Visigoths were seeking protection close to the border of the Roman Empire near the Danube against the advancing Huns. the Romans did not allow the Visigoths to cross the Danube while another tribe was awarded this extra protection. The Visigoths seized this injustice as a reason to directly attack the weakened Roman Empire [6]. By the weakened position of the Romans – by, inter alia, internal divisions – the Visigoths were able to roam for many years in Italy and even to advance to the gates of Rome. In 408 a.d., Pope Innocent I was able to prevent an incursion in Rome by negotiation and a transfer of a large ransom [7]. Around 416 a.d. the Visigoths established themselves in the former Gaul.

[8]

[8]

In Central Africa, the tensions within and between cultures were raised by internal tensions, changes in the relationships between cultures, elimination of the influence of the colonisers, artificial borders, population growth and decline and regular recurring drought. The new international order did not possess the power to intervene effectively.

This mixture of tension was in itself enough for the emergence of excesses. An unfortunate football match or an unfortunate election were sufficient for a violent eruption. But external influences enhanced the tensions and led to a catalyst for excesses.

[1] Source image: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandria

[2] Source image: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bibliotheek_van_Alexandri%C3%AB

[3] Source image: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vredespaleis

[4] Source image: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Darwin

[5] See also: Ginneken, Jaap van, Brein-bevingen – Snelle omslagen in opinie en communicatie.

[6] Source: See also: Heather, Peter, Empires and Barbarians – Migration ,Development and the Birth of Europe. London: Panbooks, 2010, p. 197

[7] Source: Norwich, John Julius, The Popes, A History, London: Chatto & Windos, 2011 p. 19

[8] Source image: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Visigoten

[2]

[2]

[6]

[6]