The next morning Carla and Man meet on the Beursplein.

“Last night I was too outspoken about Calvin’s predestination. Maybe I had the excesses in mind – e.g. the slave trade, the precipitation of revolts in the Dutch colonies, and the pursuit of capital – and I had too little attention to its merits, such as keeping livable a large piece of land below sea level and a large tolerance often based on a good business attitude. I am often too outspoken, more mildness would suit me”, says Carla.

“I admire Holland for its pictorial art, its pragmatism, its relatively good housing for everyone. This too is the result of the business attitude and God’s stewardship that has also taken shape in a socialist manner in last century. You have aptly expressed a number of starting points for derailments that were partly caused by Calvin’s doctrine of predestination. Any movement or sect that considers itself superior, has a strong tendency for derailment over time. There is Narrator”, says Man.

“Have you already been waiting a long time before this cathedral of capitalism? In many early Christian churches no regular church services take place anymore, because the believers have disappeared or have gone elsewhere. This capitalists’ cathedral is no longer in use, the followers of this religion have left for more profitable places like the South Axis in Amsterdam or the stock exchanges in London and New York”, says Narrator.

[1]

[1]

“That’s right, the capitalists pursuit maximization of profit [2], and hereby they are biting their own tails similar to players of a pyramid scheme. The sources of capital are enormous, but finite: once they will dry up.

Capitalism had already a long history before Calvinism had partially emerged from capitalism and gave further shape to it. Let me first tell you this long history in a nutshell.

Probably the meaning of capitalism is derived from the Roman word “caput” [3], which means head (of a person). This origin underlines the importance of private property within capitalism.

The onset of capitalism has probably been the use of devices by individual people to perform specific activities easier and/or faster. Among the hunter-gatherers such devices were stones to crack nuts, weapons to hunt animals and later devices combined with ingenuity to domesticate animals for food or for help during the hunt. In addition, hunter-gatherers needed a large environment as a means for their existence. When this environment or living conditions – also the possession of women and children – were threatened by other hunter-gatherers or groups of hunter-gatherers, these capital resources had to be defended.

Capitalism got a new dimension in nomadic societies of herdsmen; the capital of these nomadic herdsmen were their flocks and their pastures. The corresponding capital resources – such as animals for transport and for herding cattle – were used for tending and defending the herds of cattle, or men needed these devices – such as women and children – for survival. A religious expression within these societies of herdsmen was the cattle cycle [4]. In the Proto-Indo-European world, women represented the only possession of real value [5]; men needed the possession of livestock as a means of exchange to obtain women. In the Roman Catholic and Lutheran version of the Ten Commandments, we still see a relic hereof in the form of the ninth commandment: “Thou shalt not covet your neighbour’s wife” prior to the tenth commandment: “Thou shalt not covet your neighbour’s house” [6].

Within the agrarian capitalism of arable farming, the disposal – and later the possession of – land and water was necessary capital needed for survival [7]. In the course of time, the agrarian capitalism of arable farming has driven nomadic societies of farmers to the remote areas of Western society by occupying fixed crop lands. The introduction of the three-field system in arable farming during the early Middle Ages – in combination with limited cattle breeding – eventually allowed more people a living on permanent farmland.

Within the societies of herdsmen and farmers, bartering was needed, because people within these societies were not completely independent in their existence and because the need for specialized tools or services increased over time. There was barter needed at local markets or during fairs. The barter proceeded initially in kind; later rare objects – first rare stones or metals, and later coins with an image of a leader as trustworthy “person in the middle” – were used as “objects in the middle”.

During and after the Crusades in Western society in the second half of the Middle Ages, the trade in special items and services took further shape. Hereby, and also by the decay of feudalism arose a new economic organization during the Renaissance in Western Europe, where trade supported by the (city-)state in the form of mercantilism [8] increased further in importance. With mercantilism, the importance of coins as a trustworthy “object in the middle” also increased. Possession of coins became more and more an independent worthwhile life purpose in itself, because with money, all life goals could be obtained even remission of sins for a good afterlife through indulgences [9] within the Catholic Church.

[9]

[9]

By mercantilism, the attention within the lives of people moved more and more from “to be” to “to have”. In the earlier world of scholasticism, one was a human in a predefined order of life in which one ought to live virtuously. In the new world order, ownership of money became a great good in itself whereby a good place in life and in the hereafter could be obtained; owning and maintaining money rose in esteem, and gaining profits changed in the course of time from despicable act in a praiseworthy activity.

This form of mercantilism boomed in the Dutch Republic enormously, because of the unique position of Holland in a major river delta, because of the lack of arable farming land in Holland whereby cereals must be obtained by trade like the city-state of Athens in the fifth century BC, and because of a unique system of collective management of the polders. Additionally, the merchants and wealthy citizens in Holland – the Nouveau Riche of that time – initiated far-reaching adaptations and innovations of mercantilism.

One of the changes was the replacement of coins as “barter in the middle” by bonds [10]. Without a direct purchaser of the cargo – after examining – a shipload could be exchanged on the Dam in Amsterdam for securities. The traders in Holland did everything to perpetuate confidence in these securities

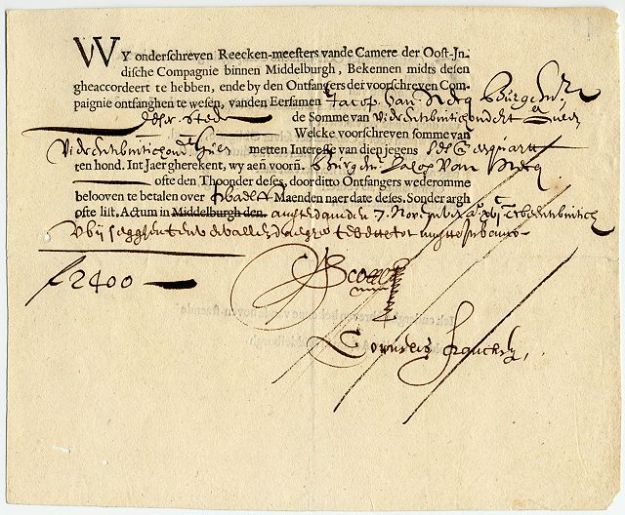

One important innovation was issuing of shares in corporations of merchants in order to make risky trading on a large scale to distant overseas colonies possible. Herewith the initiative of issuing of shares moved from nobility or (city-)state to initiatives by private individuals.

[11]

[11]

These modifications shifted the importance from coins – minted out of precious metals and imprinted with the image of a confident ruler – to securities issued by merchants and wealthy. This change shifted the economic initiative form the nobility and the (city-)state to merchants and wealthy individuals and corporations thereof.

For the “common people” of farmers, local traders and craftsmen in Holland , this new form of mercantilism meant a landslide; their whole economic existence could completely disappear in a short time by a cause from outside; others – often in modified form – may easily take over their livelihoods. They could not influence this change in any way.

Within this change of the environment of the “common people” – from a world modelled after the medieval scholasticism to a new world of mercantilism – Calvinism arose during the Reformation in relatively prosperous Geneva [12], and it found a fertile ground in the Netherlands of the 17th century AC.

By Calvinism in connection with mercantilism, the main focus of people’s lives changed from “to be” to “to have”. While in Calvinism – with its the doctrine of predestination – “being” in God’s grace was of supreme importance. But on one hand the gratitude and obligation for the elect to be God’s steward and on the other hand the constant desire for success as forecast for the election by God, meant that “to have” in earthly life is of immanent and immeasurable importance for “to be” in this life and especially in the afterlife.

In continuation of his work “Fear of freedom”, Erich Fromm states in his later work “To have or to be” [13]:

“We live in a society that is based on the three pillars of private property, profit and power. Acquiring, possessing and making profit is a sacred and inalienable right – and a duty as God’s steward according to Calvin’s predestination – of an individual human being in the new world order that has emerged from the mercantilism. Thereby it does not matter where the property comes from, nor whether there might be obligations attached to one’s property” [14].

Calvin’s predestination – embedded in mercantilism – considers “having” possessions as a predestination of God, and therefore an immutable right and duty for God’s stewards. Dorothee Sölle states in her work “Mysticism and Resistance – Thou silent screams” that Erich Fromm rightly makes a meaningful distinction between on one hand the functional properties of utensils to be used for our existence and on the other hand property for enhancing the social status of the ego, guaranteeing security in the future or just for the convenience of self-desire. About ownership of the latter kind of property, Dorothee Sölle says – I think rightly –, that it destroys the relationship with the neighbour, with nature and with the I [14]. And she states freely rendered: the forecast of a hereafter in God’s grace through the pursuit of earthly possessions soon degenerates into a prison on earth and a herald of hell. Francis of Assisi had only allowed money on the dunghill. [14]

In our modern times, paper money is exchanged for virtual bits in computer systems that offer – via monitors – access to terrestrial resources. These virtual bits had started an environment of its own, wherein mankind will be more and more a servant – or slave – to the many forms of bitcoins in these computer systems. Having access to this world of bits and monitors overshadows “being” in our daily life. Through a long detour, the emptiness of the virtual bits and monitors have confiscated the richness of our existence. This is in a nutshell my introduction to capitalism”, says Carla.

“So much in so few words in front of this cathedral of capitalism. Near this building and during your introduction, I am reminded of the haiku by Rӯokan after thieves had taken everything out from his hut:

From my little hut

Thieves took everything

The moon stayed behind [15]

The moon stands for the unshakable believe of Rӯokan”, says Narrator.

“To have or to be. After this truly somber picture of human existence. I would like to show you a different kind of emptiness: the emptiness of the Waddenzee. The next few days the weather will be good. May I invite you for the last sailing trip with my small sailboat; soon I will give the boat to a good friend who is much younger. On the sailboat we may prepare “emptiness” – the next part of our quest”, says Man.

“Shall we this afternoon look into what we still have to investigate on this part of our quest?”, asks Carla.

[1] Source image: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beurs_van_Berlage

[2] Another explanation about Capitalism is given at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitalism

[3] Source: Ayto, John, Word Origins – The hidden Histories of English Words from A to Z. London: A & C Black Publishers, 2008

[4] See also: Origo, Jan van, Wie ben jij – een verkenning van ons bestaan – deel 1. Amsterdam: Omnia – Amsterdam Uitgeverij, 2012 p. 33

[5] See: McGrath, Kevin, STRῙ Women in Epic Mahābhārata. Cambridge: Ilex Foundation, 2009, p. 9 – 15

[6] Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Commandments

[7] See also: Beyens, Louis, De Graangodin – Het ontstaan van de landbouwcultuur. Amsterdam: Atlas, 2004

[8] See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercantilism and http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschiedenis_van_Europa

[9] See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indulgence

[10] Source image: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercantilism

[11] A bond of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie from 1622 AC. Source image: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waardepapier

[12] See also: Fromm, Erich, De angst voor vrijheid – de vlucht in autoritarisme, destructivisme, conformisme. Utrecht: Bijleveld, 1973 p. 67 (Fromm, Erich, Fear for Freedom. New York: Rinehart & Co, 1941)

[13] Free rendering of paragraph from: Fromm, Erich, Haben oder Sein. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2011, p. 89 (Fromm, Erich, To have or to be?. New York: Harper and Row, 1976)

[14] Sölle, Dorothee, Mystiek en verzet – Gij stil geschreeuw. Baarn: Ten Have, 1998, p. 327 – 328

[15] Source: Stevens, John, Three Zen Masters, Ikkyū, Hakuin, Rӯokan. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1993, p. 131.